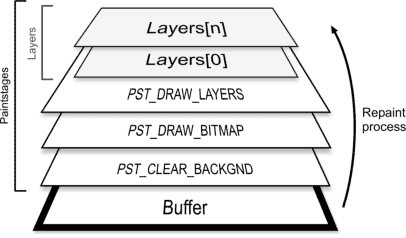

Figure 1: Paintstages at runtime

Two basic classes for on screen display exist in Graphics32: TCustomPaintBox32 and TCustomImage32. These classes provide the functionality all other graphical components in GR32 base on.

TCustomPaintBox32 implements a component similar to the TPaintBox component known from Borlands Visual Component Library (VCL). It differs from the latter in the way it handles the content: While TPaintBox directly draws to the display context, TCustomPaintBox32 uses an in-memory backbuffer. This technique generally called doublebuffering has its up and downsides: While it provides a convenient and simple way to avoid flickering by reducing many on-screen paint operations to just one synchronized buffer transfer (blit) from memory to screen, it does also require a significant amount of memory and bus bandwidth which in turn effectively limits the number of possible updates per second depending on the hardware used. The main problem with the implementation prior to version 1.8 of Graphics32 is that the whole buffer is transferred to screen even if just a small fraction of its area has changed, thus there is a lot of potential to improve on. One implementation that reduced this bandwidth was developed by Mattias Andersson as a patch called Clipping extension for Graphics32. The implementation in version 1.8 partly relies and extends on the techniques used in this patchset.

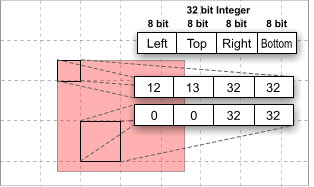

TCustomImage32 extends TCustomPaintBox32 by replacing the direct painting to the buffer with so called stacked Paintstages. Upon repaint these paintstages are executed in a succesive fashion from bottom to top - each stage drawing to the buffer.

Figure 1: Paintstages at runtime

Once a change happens in this stack at any given stage a deferred invalidation of the whole buffer content is triggered, which leads to a complete repaint of all stages once this invalidation request is handled by the application message queue in Windows. This is where the main problem resides: Even with the smallest change (e.g. an updating layer) the whole buffer area needs to be repainted. This approach - though simple - is naive and results in unnecessary CPU and bus and memory bandwidth utilitzation.

To sum up, we have two main problems to overcome, i.e. to optimize:

In order to achieve this, we need to restructure the repaint process in both, TCustomPaintBox32 and TCustomImage32. An external repaint optimizer should take care of the aspect of managing and optmizing changed areas. This abstraction allows better flexibility over an in-place implementation, because the repaint optimizer can be exchanged freely.

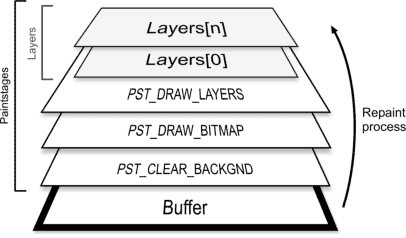

TCustomPaintBox32 implements a new property RepaintMode that allows selection of the repaint mode to be used. rmFull is equal to the old full scene repaint whereas rmOptimizer uses the repaint manager to handle only updated areas.

Figure 2: Example comparison of full scene and optimized repaint

Figure 2 shows an example comparison of the old full scene repaint (rmFull) and the new optimized repaint (rmOptimizer) for simple layer operations like moving or resizing. One can see that the new method breaks the full scene repaint down to just a fractional repaint namely those parts that were changed. Both modes are used in TCustomPaintBox32 for repaint to screen and in TCustomImage32 for repaint to buffer. Additionally there is one mode called rmDirect which is only available for TCustomPaintBox32 derived controls and does provide a direct repainting to screen. In this mode the deferred repaint technique is replaced by an immediate repaint. This technique is especially useful for the new TSyntheticImage class, which provides incremental painting of the result while still rendering.

Layers in Graphics32 are a special case that needs to be taken care of separately: Since layers are not forced to stay within their determined bounds (for TPositionedLayer for example), they can basically paint everywhere on the buffer. Thus we need to find some other way of determining which areas the layer is drawing to. For this to work we have extended all safe drawing operations in Graphics32 to support a method called measuring. This method can basically be thought of as a simulation mode or dry-run where nothing is actually drawn to the buffer. However, the Changed event is still triggered. So, this way the repaint optimizer can get information of which areas the operation is drawing to. As a matter of fact the repaint optimizer just needs to iterate through all marked layers (compare Figure 2), calling the Paint method of each layer with the measuring mode enabled. The information gathered in this process is used for the repaint manager's internal optimization work, ie. unifying overlapping areas and minimizing the number of rectangles to be updated.

Profiling has shown, that the measuring process adds only neglectable overhead to the repaint process. However, the developer needs to take care of certain facts in his custom code to actually take advantage of the performance benefits the repaint optimizer offers.

begin

MyDrawingOperation(Buffer);

Buffer.Changed;

end;

begin

if not Buffer.Measuringmode then

MyDrawingOperation(Buffer);

Buffer.Changed(RectOfAreaThatWasChanged);

end;

Code 1 compared to Code 2 illustrates the required changes in pseudo-Pascal-code. As seen in the Code 2, a simple check for active measuring mode is introduced. In this case the actual drawing operation is omitted.

If the developer's code includes calls to the Changed method, those calls need to be changed to only represent the changed area instead of the whole buffer area. Keeping the Changed method unmodified will force a complete buffer invalidation, thus the effect of the repaint optimizer and the partial repaint therefore is reversed. Also, the custom code needs to be fully safe, meaning it has to offer full clipping support.

If the developer's custom code solely relies on the safe drawing operations provided by Graphics32, there is no need to change this code. However, doing so will likely result in better performance especially if the custom code is calling many safe drawing operations. In this case introducing the changes of Code 2 could simplify the measuring process a lot by overriding all subordinated checks by one superordinated check for measuring mode.

So, to sum up, there are two possible pitfalls in custom code that can occur with the new optimized repaint approach:

As already mentioned above, the repaint optimizer is responsible for managing and optimizing changed areas, which are described by rectangles. Because there can be quite a lot changes happening between repaints, the area information has to be saved in a space-saving and performance-optimal structure.

The naive approach of saving all rectangles into a list and combining them once the repaint optimizer's method PerformOptimization is called is not suitable. With each TRect instance being 16 byte in size, the memory usage is unacceptable for large sets. The overhead of reallocating such structures is also noticeable. Moreover one has to make sure not to add several overlapping rectangles to the list. Using an algorithm for this matter adds complexity to the process. Thus, we need to find a better and more flexible way of managing possibly overlapping reactangles.

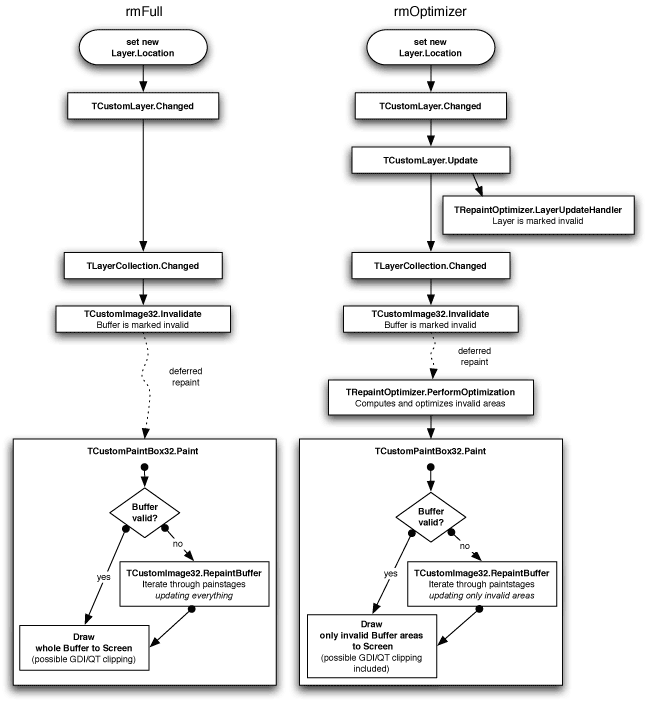

Figure 3: Granularity comparison of MicroTiles and Tiles

A totally different approach is to subdivide the buffer's dimension into a matrix. Each tile of this matrix would be responsible for a 32 x 32 pixel area in the buffer. New rectangles would simply be rendered to this matrix. The memory usage stays constant because the matrix size is in fixed relation to the size of the buffer size. Also, the problem of handling overlapping reactangles is also easily solved by rendering to the matrix. Additionally unifying tiles to bigger rectangles is obviously less complex than the approach needed for determining and unifying reactangles from a list structure. However, because each tile of our matrix only holds a binary value (filled or emtpy), the granularity (compare Figure 3) of this approach is quite high and thus too much information is lost.

The method used in Graphics32 1.8 is based on the tile method but improves the granularity problem by expanding each tile in the matrix from a binary representation to an integer representation.

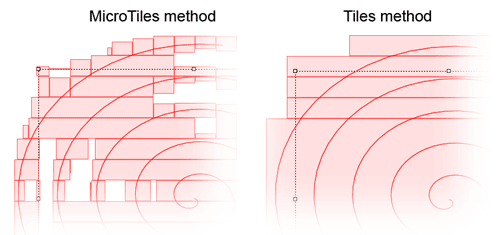

Figure 4: Rectangle rendered to 32 x 32 Pixel MicroTiles

So, instead of only having to restrict to full or empty as possible values, the tile contains exactly one rectangle that can further define the content. The two 16-bit values in the 32-bit integer of each tile represent the upper left and lower right corner of the inscribed rectangle relative to the upper left position of the tile (Figure 4). This allows a finer granularity and in the worst case (tile completely filled with one inscribed rectangle) the solution equals the tile based approach. However, most times the result is better, thus more information about the original shape is kept.

Because each coordinate is 8-bit wide, the tile size can scale up to 256 x 256 in size.

This method was first implemented by the developer of libart by the name MicroTile Arrays. Graphics32 implements an optimized version of its own and mixes that with some specialities: The MicroTiles Repaint Optimizer implements a simple adaptive algorithm that chooses between full scene, tile and MicroTile based operation mode depending on the current update situation.

For instance with many small rectangles (500+) the MicroTiles based optimization becomes less effective and can pose a performance overhead. In this case the adaptive algorithm will automatically downgrade to the next lower mode, which in that situation is the tiles based mode. Because the granularity is bigger in this mode, the optimization process is also less complex. Once the situation normalizes, it switches back to MicroTiles based operation mode. Thus, a good performance should be guaranteed in almost all cases.

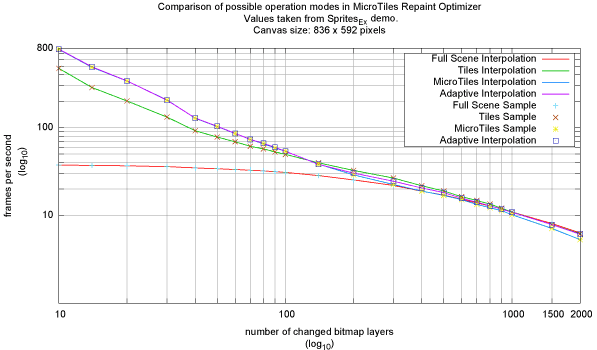

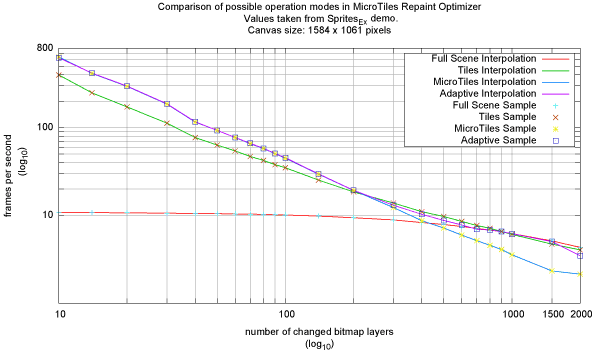

The Sprites_Ex project was the most important test case of all because it is exceptional in the way that it shows both, the strength and weaknesses of the MicroTiles based approach. For our tests we've extended the project slightly to be able to measure the effective frames (or updates therefore) per second.

(a)

(b)

Figure 5: Benchmark results with Sprites_Ex on PIII 1.13 GHz, WinXP, Geforce 2 mx

Figure 5 shows two results of benchmarking with different canvas resolutions. Each bitmap layer has a size of either 32 x 32 or 64 x 64 pixel picked randomly. The random seed used in the benchmark is reproducible for each test machine, thus a valid comparison is possible. As seen in the first graph (a) the MicroTiles based optimization works considerable better than the Tiles based approach. However, on our test machine it becomes less effective starting with 70 changed layers and finally the Tiles based approach outpaces it starting from 130 changed layers, because the higher granularity helps while combining the tiles to uniform rectangles. Using the MicroTiles based approach results in too many rectangles, which in this situation are less effective than fewer combined rectangles. This trend continues up to 600 rectangles. The Tiles based approach finally converges against the full scene repaint with MicroTiles being slightly worse due to the overhead involved. With so many layers the canvas area is almost completely covered with updates. For Graph (b) the results are slightly shifted due to the bigger canvas size. Both graphs show that the adaptive approach works well enough to be a feasible solution, however, the overhead of the balancing and scheduling used is noticeable in the switching regions of the graphs.

Paint Stages, Examples, TSyntheticImage, TCustomImage32, TCustomPaintBox32, TCustomPaintBox32.RepaintMode, TRepaintMode

Copyright ©2000-2024 Alex Denisov and the Graphics32 Team - Graphics32 2.0 - Help file built on 18 Feb 2024